BlogTuesday, December 06 2022

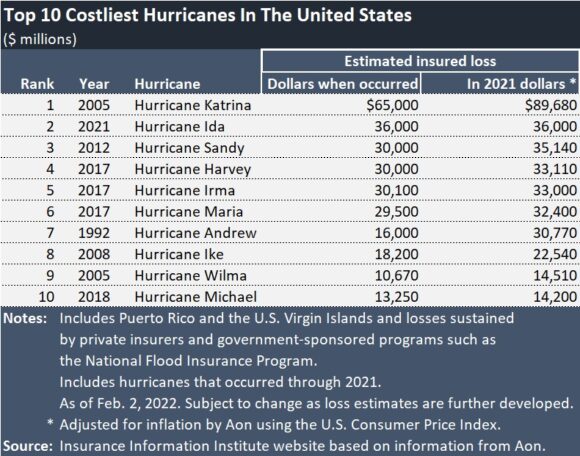

Hurricane Ian didn’t break Florida’s property insurance market. Insurers have the capacity to pay claims from the storm, which struck Southwest Florida last month as a Category 4 hurricane that destroyed hundreds of structures and killed more than 100 people. Losses estimated by domestic insurers have been readjusted this week to levels lower than originally estimated and experts say those losses will remain well within companies’ abilities to pay claims. They’ll be doing so out of their surpluses and reinsurance they were able to secure before this year’s hurricane season. That’s the good news. The bad news is that numerous insurance experts predict that the state legislature will need to take more action to shore up the industry before the 2023 hurricane season, possibly by pledging more public funding to ensure companies can maintain required funding levels. Ian is still expected to be one of the nation’s costliest storms ever and will increase costs of reinsurance — that is insurance that insurers buy — before the next two rounds of reinsurance renewals on Jan. 1 and June 1. And those higher costs will be absorbed by homeowners across the state next year, regardless of whether they were unfortunate enough to live in Ian’s path or in a part of the state that emerged relatively unscathed, as South Florida and the Panhandle did. “Everyone is going to have to pay some increase,” says Paul Handerhan, president of the Federal Association for Insurance Reform, a consumer-focused watchdog group that advocates for legislative changes that it sees as necessary to keep insurance available and affordable in the state. How much more we’ll be paying next year remains to be seen. But it will be yet another punch in the pocketbook for homeowners who have seen their insurance premiums roughly double over the past five years to about three times the national average. Average annual premiums this year topped $4,000 in five Florida counties, including Broward, Palm Beach, Miami-Dade and Monroe, state data shows. Projected losses less than fearedEstimates for Ian’s insured losses are wide ranging, from a low of $30 billion to more than $75 billion. Stonybrook Capital recently said that Ian could cost $75 billion or more, making it the third-most expensive insured event in U.S. history, behind only the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001 and 2005′s Hurricane Katrina. Catastrophe modeling firm Karen Clark & Co. projects insured losses of $63 billion, except for flood losses covered by the National Flood Insurance Program. Analytics firm RMS projects insured losses will land somewhere between $53 billion and $74 billion, excluding NFIP-covered flood losses, companies’ loss adjustment expenses, auto and marine losses and inevitable costs of litigation. Several domestic insurers, including publicly traded Heritage Property & Casualty, Universal Property & Casualty, and Homeowners Choice, have released statements projecting that their losses won’t exceed their abilities to cover them out of of their surpluses and available reinsurance. Stacey Giulianti, chief legal officer at Boca Raton-based Florida Peninsula Insurance, says insurers have reduced loss estimates after two weeks of damage inspections along Ian’s path. One reason is that despite Ian’s deadly storm surge, its actual hurricane-strength wind field had a much tighter radius than other recent storms, Giulianti said. After destroying structures in Fort Myers Beach, Cape Coral and low-lying parts of western Fort Myers, the storm’s winds rapidly weakened as moved over sparsely populated agricultural and preserve land. “Virtually every carrier has slashed their projected ultimate losses by a huge percentage,” Giulianti said. “Reinsurance will cover this storm easily for domestic carriers with plenty of room to spare should a late season cyclone threaten the peninsula. Except for the first 24 hours after landfall, we have seen claim reports drop dramatically and have had essentially zero telephone wait times in our claims department. “This storm is unlikely to knock out any conservative insurance carriers that have sophisticated reinsurance towers and ample surplus.” State-owned Citizens Property Insurance Corp., the insurer of last resort, has revised its Oct. 5 projection for total number of claims from more than 225,000 to 100,000. “We initially estimated that damage and claims numbers would be far greater outside of the three-county area of Lee, Charlotte and Sarasota counties than we are seeing at this point,” spokesman Michael Peltier said. Its projected loss estimate remans at $2.3 billion to $2.6 billion “until we can base it on actual losses,” Peltier said. If losses remain at those levels, CItizens won’t have to recover any shortfall from its own policyholders or from insurance consumers statewide with levies or special assessments. Florida’s Hurricane Catastrophe Fund, which provides reinsurance that companies can tap after exhausting their privately funded reinsurance, could be forced to pay between $10 billion and $12 billion of its $17 billion claims-paying capacity, says Locke Burt, chairman and CEO of Ormond Beach-based Security First Insurance Co. That would have to be replenished but can be done so over several years, through the fund’s purchase of long-term bonds and ability to levy surcharges on private-market policies. Flood losses from Ian’s storm surge were estimated by CoreLogic at between $8 billion and $18 billion for residential and commercial properties. Uninsured flood loss is estimated to be between $10 billion and $17 billion. But those losses won’t impact Florida property and casualty insurers because flood insurance is covered by the National Flood Insurance Program and private carriers. Reinsurance will be harder to getEven before Ian hit, Florida insurers struggled to buy enough reinsurance to guarantee their ability to pay claims after two major storms, including a 1-in-130-year hurricane that has never before happened. The closest was the Great Miami Hurricane of 1926 that caused the equivalent of $235 billion in damages and killed 372 people. Six insurers went insolvent this year, in part because they didn’t have enough capital to secure reinsurance levels required by state insurance regulators and Demotech, an Ohio-based agency that assigns financial strength ratings for federal loan guarantors Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. Those loan guarantors require properties in their portfolios to maintain “A” strength ratings. Reinsurers are typically based overseas, in places like Bermuda, and are unregulated by states or the federal government. That means they can sell as much or as little coverage as they want, factor in whatever risks they fear, and charge anything they want for the coverage. Lately, with severe weather events becoming more frequent and more destructive, Florida insurers have been losing money and reinsurers have been willing to sell less coverage and demanding more money for it, Handerhan said. Reinsurers’ appetite for Florida risk is likely to shrink even further after Ian, largely because Florida’s army of plaintiffs attorneys makes catastrophe risk modeling impossible, industry experts say. While just 9% of the nation’s homeowner insurance claims are generated by Floridians, 79% of all lawsuits against homeowner insurers originate here, the Florida Office of Insurance Regulation has reported, using data from the National Association of Insurance Commissioners. High litigation rates after major storms like 2017′s Irma, a slow-moving storm that caused damage throughout the state, and 2018′s Michael, which hit the Panhandle with Category 5 strength, created greater losses than reinsurers initially estimated. Stonybrook Global’s $75 billion loss estimate, which it says was derived by averaging projections from major catastrophe risk modeling firms, assumed that litigation would increase actual loss costs by another 20%. The firm estimated that Ian will wipe out a year’s earnings for global reinsurers and result in double digit operating losses for domestic companies. Looking forwardThe biggest risk facing property and casualty insurers in Florida will come well after Ian’s debris is hauled away and rebuilding efforts have commenced: How many insurers will be financially healthy enough to secure needed reinsurance for next year’s spring storm and summer hurricane seasons? Like this year, some companies might not be able to raise the needed capital to satisfy Demotech and the Office of Insurance Regulation and will likely go insolvent, Handerhan predicted. “It’s going to be a huge problem. If they can’t get reinsurance, you could see more insolvencies,” he said. Companies strong enough to make the buys will pay more. Last year, most insurers paid 50% more to renew their reinsurance policies, “nearly double other coastal states because of litigation cost risk,” said Mark Friedlander, communications director for the Insurance Information Institute, a nonprofit funded by major national insurers. Another special session?Friedlander says the Florida home insurance market is in crisis “because of manmade issues, not natural catastrophes.” He adds, “Roof replacement claim schemes and excessive litigation have led to the market’s deterioration.” Calls are growing for another special legislative session to finish what lawmakers failed to accomplish during the most recent special session in the spring. Then, lawmakers enacted a number of attempted fixes, including creation of a special $2 billion optional reinsurance fund backed by the state’s general fund. Insurers were also allowed to offer depreciated roof value coverage instead of full replacement value coverage. Insurers say they’ve lost millions because standard homeowner policies require full roof replacements if more than 25% of a roof is damaged. The generous coverage incentivizes roofing contractors to “find” damage and sue insurers for the cost of full roof replacements, insurers say. Another special insurance session could include legislation finally killing Florida’s unique one-way attorney fee statute that insurers blame for the state’s disproportionately high litigation rates. The statute removes most of the risk of suing insurers by requiring insurers to pay all plaintiffs attorney fees if a lawsuit produces a settlement for any amount of money over an insurer’s initial offer, but does not require the plaintiff to pay the insurers’ fee if the insurer wins. Citing similar reforms enacted recently in Texas, proponents say numbers of predatory lawsuits in Florida would drop sharply if plaintiffs had to consider out-of-pocket losses before suing. Such a reform would likely restore profitability to many insurance companies, boost confidence of investors, and increase reinsurers’ willingness to underwrite Florida storm risks. But Handerhan said killing the one-way attorney fee statute would also hurt homeowners’ abilities to get their damages repaired because they would have to pay their attorneys out of their ultimate claim settlement, potentially leaving them unable to pay for their repairs. Amy Boggs, insurance section chair for Florida Justice Association, a trade organization for plaintiffs attorneys, said in an email that litigation rates have already declined 30% as a result of reforms enacted since 2019. “However, there have been zero improvements in the insurance marketplace for consumers, nor a lowering of insurance rates after those reforms.” The association, she wrote, “does not see that further litigation reform will do anything to improve the environment for Florida’s homeowners” and could instead put them in an even worse situation when their insurance company decides to ‘underpay, delay and deny’ payment of meritorious claims.” Yet some insurers say they are already hearing attorneys say they plan to file suit to challenge findings that losses were caused by storm-surge flooding rather than by hurricane winds. On the Fox Weather Channel recently, attorney Andrew Lieb described that strategy, saying, “The question becomes, Did the flood happen because your roof was ripped off and that was a wind issue and not a flood issue? Or did it come from a surge and that’s a flood issue?’” In her email, Boggs said, “We already see finger pointing by insurance companies on wind versus flood due to Hurricane Ian.” FAIR: Two important fixes neededHanderhan said FAIR would like to see a special session focus on two remedies. One would eliminate annual rate-increase caps that were put in place for Citizens policies in 2008 by then-Gov. Charlie Crist. At the time, the caps were intended to protect Citizens customers from insurance cost increases. But as private-market companies have been forced to increase their rates far beyond the Citizens cap, Citizens has become a much-cheaper alternative and an unfair competitor, proponents of eliminating the cap say. The other needed reform, Handerhan said, will be to make more state-backed reinsurance available to ensure private-market carriers can survive until recent legislative reforms take effect in two or three years. One way to make more reinsurance available would be to lower the amount of hurricane losses companies would have to endure before becoming eligible for reinsurance through the state Hurricane Catastrophe Fund. FAIR has argued for such a change over the past three years, saying it would keep costs down by allowing insurers to buy less private-market reinsurance. Another way the state should fund more reinsurance would be to create a larger version of the Reinsurance to Assist Policyholders (RAP) fund that made $2 billion from the state’s general fund available to insurers that had trouble finding enough reinsurance on the private market. How much money should be committed depends on how much would be needed, he said. Flush with cash right now, the state can afford to create a larger reinsurance fund to ensure that the industry and the real estate market survives the next storm season, Handerhan said. John Rollins, former chief risk officer at Citizens and current director of ventures at Texas-based Evans Insurance Group, said he expects Florida’s brightest minds will hash out solutions before the start of the 2023 hurricane season. “Unlike in most states, our insurance leaders also live, work, and employ people here, and we have the best talent on the planet to deal with this challenge,” Rollins said. “Likewise, I think our public sector is well stocked with expertise. As with an approaching hurricane, it’s not time to panic, it’s time to prepare.” Monday, December 05 2022

It hasn’t been made official by the governor’s office, but Florida legislative leaders have set a date for a second special session to tackle property insurance issues – Dec. 12 through Dec. 16. Memos from newly sworn Senate and House leadership show the date coincides with already-planned plenary and organizational meetings for the 2023 regular session of the Legislature, which starts in March. A formal proclamation on the special session is expected this week. The memos did not address what reforms may be on the agenda, but insurance industry lobbyists, news reports and comments from legislative officials suggest that lawmakers may squash one-way attorney fees altogether in claims litigation; may further limit assignment-of-benefits agreements; provide a layer of state-backed reinsurance for carriers; and make some adjustments to the Florida Hurricane Catastrophe Fund, perhaps allowing easier access to the fund’s reinsurance. New House Speaker Paul Renner, R-Palm Coast, last week said he is aiming for “systemic reform” that will shore up the private market and steer policyholders away from the ballooning, state-created Citizens Property Insurance Corp., according to Florida Politics news site. He also did not rule out using tax dollars to provide lower-cost reinsurance for insurers, which are now facing another round of double-digit price increases from private reinsurance firms. Many in the insurance industry have advocated for a lower cat fund retention level, or lower deductible, for carriers, to allow them to access the fund sooner, saving them significantly on reinsurance costs. But after Hurricane Ian hit Florida in September, the cat fund may be forced to go to the bond market and borrow billions of dollars to replenish its statutorily required reserve funding. Now, an influential business group is warning to lawmakers to stay away from tinkering with the fund. “Expanding the size and scope of the Florida Hurricane Catastrophe Fund sends an unfortunate signal to private reinsurance markets that their capital is unwelcome,” reads a special session priorities briefing from Associated Industries of Florida, which represents a range of manufacturers and other businesses. “Policymakers should guard against efforts to adjust its coverages at the expense of depleting its cash build-up,” which could make it more likely that Floridians and business owners could see another surcharge or “hurricane tax.” AIF made similar statements before the 2022 regular legislative session in January. If the Dec. 12 session is anything like the first insurance-dedicated special session, held in May, the reform package will be crafted by legislative leaders and the governor’s office shortly before the session begins. In May, the proposed bills were unveiled less than 48 hours before the Capitol opened, and the bills sailed through in three days with almost no changes. Monday, December 05 2022

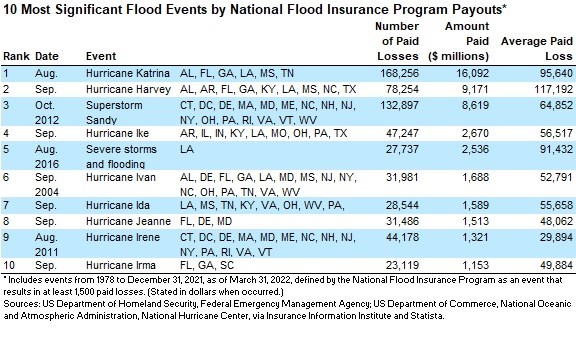

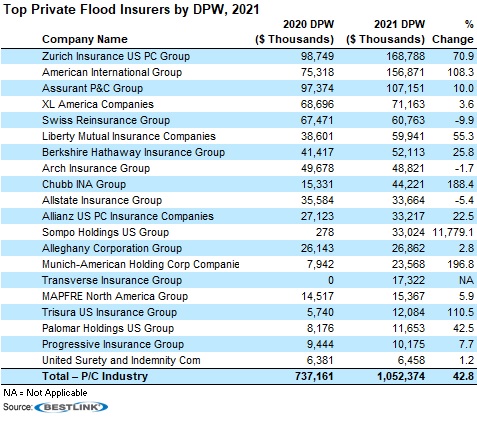

Hurricane Ian may result in one of the largest losses in the history of the National Flood Insurance Program and add to its current $20.5 billion debt. According to a market segment report from AM Best, the projected range of Hurricane Ian losses of between $3.5 billion and $5.3 billion from the Federal Emergency Management Agency would potentially be below the program’s reinsurance attachment. But recent estimates from modeler CoreLogic are much higher – breaching and perhaps blowing through the reinsurance layer. CoreLogic said flood losses from Ian, which made landfall in Florida on Sept. 28, could be between $8 billion and $18 billion. Hurricane Katrina in 2005 caused $16.1 billion in losses to the NFIP, the most ever (see chart). The NFIP had to borrow $17 billion to pay claims related to Katrina and hurricane Rita and Wilma, which also struck in 2005. Hurricane Nicole, which also struck Florida after Ian, will result in additional losses. AM Best report titled, NFIP Adrift but Private Flood Insurance Gains Traction, also pointed out that private flood insurers increased direct premiums written by 42% in 2021, the first year Risk Rating 2.0 was implemented to allow for more adequate rates and make private flood insurers more competitive. However, the private flood insurance market remains one-third the size of the federal flood market. Last year 88% of Florida homeowners with flood insurance saw an increase in NFIP premiums and many will see additional rate increases in 2022 and 2023, “likely driving even more homeowners into the private flood insurance market,” AM Best said. “The full effect of Risk Rating 2.0 has not yet been reached,” the insurance industry rating agency said. “Premium increases are capped at 18% a year on single family primary residences. Based on the limitations on incremental rate increases, the flood premium for many homes will not reach their full actuarially sound rate for another four years.” Thursday, December 01 2022

Florida’s homeowners shell out thousands, even tens of thousands, for property insurance to protect themselves from fierce storms like Hurricane Ian. But tens of thousands of people walloped by the Category 4 storm in September are now discovering that they didn’t have the coverage they needed for one of the biggest impacts of the storm — flood insurance. It’s one of the hardest — and most expensive — lessons from hurricane season 2022, which officially draws to a close Wednesday. Florida’s home insurance market has been troubled for decades, but experts worry that the back-to-back strikes from hurricanes Ian and Nicole could be enough to tilt the teetering market for wind damage insurance into another collapse. Gov. Ron DeSantis has hinted at holding another special session on the topic soon, but it’s not clear if legislators will even try to address the already skyrocketing costs of private insurance and increasing risk load of the state-run option, the Citizens Property Insurance Co. And even if they do, coverage for Florida’s most common risk — flooding — won’t be on the table for discussion. Flood insurance is almost entirely run by the federal government, which sets strict rules and price caps on who needs to have it and how much it costs. Experts say that despite the government’s efforts to make flood insurance cheap and available, Florida faces a massive coverage gap that could grow even larger as the state’s population — and flood risks — grow and the number of policies slowly declines. By one estimate, flood damage could make up half of the total Hurricane Ian losses in Florida. The Category 4 storm tore into Southwest Florida in late September, battering Fort Myers and other areas with two-story storm surge and fierce winds. But it was the slow creep north through the rest of the state, when the much weaker storm dumped more than a foot of rain, that shocked inland residents. Low-lying areas quickly flooded, leaving some apartment complexes with an entire story underwater. Officials had to rescue more than a hundred residents trapped in their homes and cars. The Peace River, in Southwest Florida, swelled from 130 feet wide to nearly a mile wide. And when the floodwaters eventually receded, many Floridians in the path of Ian — and then Nicole — found they weren’t covered for the damages. Only about 18% of homes in Florida counties that were under evacuation orders from Hurricane Ian had a federal flood insurance policy, according to an analysis by risk management firm Milliman. In inland counties, those figures drop even further. Compare Lee County, where Ian made landfall, to Seminole County, north of Orlando. In Lee, about 51% of properties inside flood zones have flood insurance. In Seminole, only 37% do. In either case, that leaves thousands uninsured for flooding damage outside the coverage of most homeowner and windstorm policies. Claims will likely be rejected. “People just expect to be protected and it’s very distressing and upsetting for them to find out they paid the premiums and don’t have the coverage they need,” said Nancy Watkins, a principal and consulting actuary with Milliman. “Often the reason they don’t have a flood insurance policy is they mistakenly think that their homeowner policy would cover that.” Few home insurance policies cover flood damage. Instead, almost all flood insurance policies in the nation are through the FEMA-run National Flood Insurance Program, which insures 1.7 million Floridians. The state actually has the highest number of flood policies under the federal program, but hurricane season 2022 was a sobering reminder of how many people don’t have it. An early estimate by CoreLogic, a property information and analytics firm, suggested that half of the flood damage Florida saw from Ian could be uninsured. Tom Larsen, CoreLogic’s vice president of hazard and risk mitigation, said his firm also found Ian’s damage in Florida extended outside FEMA’s flood zones. “We saw more damage outside those zones than in,” Larsen said. “It doesn’t take much water to cause a lot of damage.”

How much damage did the hurricanes do?Florida’s Office of Insurance Regulation has tallied nearly $10 billion in total losses from Hurricane Ian so far. That includes losses to homes, commercial properties and private flood insurance claims. Initial estimates from FEMA suggest the federal flood insurance program, which insures the vast majority of Floridians with flood policies, could see $3.5 billion to $5.3 billion in losses from all five states hit by Ian, with the majority of those claims coming from Florida. Florida’s relatively small private flood insurance market, with just under 100,000 policies as of late 2021, also took a hit. Trevor Burgess, CEO of Neptune Flood, said his firm has about a third of Florida’s private flood insurance policies. He ranked Ian as the most expensive storm the firm has dealt with since it started five years ago but didn’t offer a dollar figure estimate. “Ian will be our largest claim event after Ida last year,” he said. “Having them year after year is consequential.” For Hurricane Nicole, Florida’s total property losses are slimmer but still significant at just under $400 million. What does flood insurance cover?For the lucky few that had the proper insurance to match their hurricane-borne flood damage, there’s cash from FEMA on the line in at least a few ways. As of mid-November, FEMA said more than 40,000 Floridians have filed Ian-related flood damage claims. They’re likely to get some help patching up their homes, but it likely won’t cover a full replacement. The NFIP, like many of the private flood offerings, is capped at $250,000 of coverage. The picture is worse for those without flood insurance. “An inch of water in your house can easily be a $25,000 expense,” said Watkins. Uninsured people will have to raid their savings or hope for help from charities or state and county grants. Federal grants are not an option. FEMA reserves its grant programs for fixes like home elevation or floodproofing for those with active flood insurance policies. FEMA disaster relief for uninsured properties is usually capped at around $10,000, Watkins said, and it can take a very long time to materialize in people’s bank accounts. Flood insurance numbers droppingYet despite the growing risk of flooding — which Watkins says is the most common disaster facing Floridians — the Sunshine State has fewer and fewer residents with flood insurance every year. Burgess, with Neptune, said his firm produced data showing that 18% of Florida buildings had flood insurance five years ago, and today that figure stands at 15%. “That’s going in the wrong direction. We need many many more people to buy flood insurance to be protected from this peril,” he said. That’s a tough sell in Florida, even considering that sea level rise is making nuisance flooding more common and more intense. The biggest reason is likely that flood insurance, unlike property insurance, isn’t mandatory for most homes. Any home purchased with a mortgage is required to have property insurance, but mortgage-purchased homes are only required to have flood insurance if they’re within a designated FEMA flood zone. And even then, research shows that many of the properties required by their lenders to hold flood insurance policies drop them with no consequences. A recent revamp of the federal flood program, known as Risk Rating 2.0, aims to get more people insured at market rate premiums, a move that could help the NFIP dig itself out of its $20 billion debt hole. For Joel Scata, an attorney with the Natural Resources Defense Council’s water and climate team, the flood damage from Hurricane Ian is another indication that the federal program needs to be reformed to encourage people to live farther away from risky areas. “Floods, in general, are becoming more frequent, both inland and on the coast, because of sea level rise and intense rainstorms,” he said. “The NFIP has the opportunity to be a linchpin in the U.S. approach to mitigating flood risk in regards to climate change.” Average flood insurance premiums are around $600 a year in Florida, according to data collected by Forbes. That makes Florida one of the cheapest states in the nation for flood insurance, despite home and windstorm insurance premiums that are some of the highest in the nation at more than $4,000 a year. “People don’t want to pay more money to buy more coverage that they don’t have now,” Watkins said. “But you don’t find out you need it until it’s too late.” Monday, November 14 2022

As the Florida Legislature prepares for its 2nd Special Session on property insurance in 2022, it’s time we examine why our market sputtered out of control and discuss the necessary solutions to fix it. Many Floridians are wondering:

Media outlets across the state have done a decent job of highlighting the failing insurance market. However, there are many misconceptions associated with these reports. The first, that storms are to blame, and the second, that reinsurance rates are exploding due to climate change. In truth, many factors have contributed to the crisis and the insolvent companies failed or were failing long before the 2022 Hurricane season even began. Reinsurance rates have risen, but the cost that can be passed onto the consumer is statutorily capped at 15% per year. While considerable, that only accounts for 60% of the 300% in rate increases since 2018. In short, this crisis starts and ends with litigation. Most have likely seen the headlines that Florida accounts for 80% of our nation’s property insurance lawsuits, while only accounting for 8% of the claims. Breaking that data down further shows that every other state averages less than 1,000 lawsuits annually, while Florida averages 100,000. This leads us to the multi-billion-dollar question: How? This question merits a complex answer, for sure, but can be boiled down to this: The combination of assignment-of-benefits (AOB) proliferation, an obscure, 2016 decision by the Florida Supreme Court (Sebo vs. American Home Assurance), and the 100-year-old one-way attorney fee statute (627.428), created a perfect legal storm so great that it brought our state’s insurance market to its knees. A layman’s attempt to describe each is as follows…

AOBs have been often utilized in healthcare. You go to the doctor, and you assign your benefits to them so they can work with your insurance company for billing purposes. One day a few Florida attorneys figured out they could apply this practice to a homeowner in need of a fast repair, and assume complete control of a claim, including the ability to file a lawsuit. And, Voila! A massive incentive was created from thin air and a cottage industry was born. Prior to 2010, the state saw about 400 lawsuits annually, but once the AOB scheme was unleashed, that number ballooned to 30,000 in 2016. It took strong words from Gov. Ron DeSantis, in his very first State of the State address in 2019, to move the needle on moderate reform when he declared that AOB’s “had degenerated into a racket.” Unfortunately, by then, this racket had already metastasized out of control. This then brings us to the 2016 Sebo decision by the state Supreme Court, which replaced the long-standing and efficient proximate cause doctrine with the concurrent causation doctrine. In practical terms, this enabled contractors to find very minimal damage on already deteriorating roofs or buildings and claim that the small damage, combined with the crummy condition of the structure, necessitated a full replacement at insurers’ expense. So, one windblown shingle on a 20-year-old roof was artfully used to get someone a new roof for “free”. Now, let us factor in the holy grail — one-way attorney fees, courtesy of Florida Statute 627.428. The way this statute works is relatively simple: If you sue your insurance company and the case goes to trial, you only need to win $1 more than their last pretrial offer, regardless of the amount for which you were suing. If successful, the homeowner will be compensated for all attorney fees at the insurance company’s expense. This fee structure, hailed as the David vs Goliath statute, was created to level the playing field so the Smith Family (David) could fight back against Big Insurance Co. (Goliath). For decades, it was considered to be a fair and reasonable concept.

Essentially, nothing prevents a contractor from coming to your home and assuming your rights, finding minimal damage yet filing a large claim; and then working with a lawyer to inflate the claim higher to garner a huge settlement. Financially, it works like this: They sue an insurer for $100,000 for a new roof that, if legitimately damaged, costs $25,000. But it has only two shingles missing that should cost $150 to replace. The insurance company must meet in the middle and settles for $65,000 because it would cost more to go to trial. Now multiply by 130,000, which is the number of lawsuits filed last year, according to state Department of Financial Services data. That equates to more than $8 billion and a healthy dose of eyeball emojis. Now you might find yourself saying: “How can these insurance companies claim poverty and any of this be true when 4 out of 5 television commercials is an advertisement for an insurance company?” The answer is that those “national” carriers combine for only 10% of the market share in Florida. This has been the case since the 2004-2005 hurricane seasons when Mother Nature alone was cause for concern. Citizens Insurance is now the largest provider in the state with more than 15% of the market share. “Domestic” (Florida-only or predominant) carriers are the primary source of homeowners insurance in the state. These insurers, national and domestic, are not without blame, either. Despite the ongoing multibillion dollar racket being committed against them, many carriers that went belly up did so because they ignored the most fundamental aspect of insurance, risk management. The few companies that have weathered this market responsibly did so because they chose to sacrifice growth to protect solvency. The now-defunct carriers were 2-3 years too late when it came to tightening their underwriting practices. It is also unfathomable that some companies would pay not just normal, but increased, dividends or investor bonuses at a time when their company surpluses were being depleted by the tens of millions annually. Even worse, some took on debt to do so. Regardless of the reforms enacted in December, there will be more insolvencies and the number of existing companies on stable ground moving forward can be counted on one hand. The topic of insurance can seem boring, but it is essential state infrastructure. It is the oil that keeps a free-market engine running, and it is safe to say Florida’s property insurance market needs an oil change! What should the new synthetic blend look like? Thus far, the state has tried three times since 2019 to halt abusive practices: AOBs were first regulated to allow for a 14-day rescission period and a new fee-shifting measure for third-party lawsuits was put in place. Then in 2021, a hybrid version of that fee structure was enacted for first-party lawsuits and the amount of time to file a claim was lowered from 5 years to 2 years. Finally, in the May 2022 Special Session, one-way attorney fees were eliminated altogether for AOBs, attorney fee multipliers were prohibited, and building-codes for roofs were updated to combat the loophole being exploited post-2016 and the Sebo case. Has it worked? Some, but not quick enough. Thankfully, Hurricane Ian did not deliver a death blow to the insurance industry partly because these previous reforms had been enacted. Each reform was a tough battle brought forth by good legislators and none made it across the finish line without the governor’s vocal support. However, just surviving Ian is not good enough because Floridians know there will always be more hurricanes on the horizon. To stabilize the marketplace for the foreseeable future, the one-way attorney fee must be abolished across the board, just as it is in most other states. Other changes: Price and scope arguments can be resolved through arbitration or independent appraisals. The time frame to file a claim should be lowered to one year and any assignment of rights, benefits, etc. should be banned completely. Litigating when an insurance company has truly engaged in bad-faith practices should be allowed to continue. If these measures happen, we will slowly get back to normal — or as normal as Florida can be. The better in-class carriers will begin to grow again, pressure on Citizens will be relieved, and new capital will form to enter the state and fill the void left by insolvencies. Reinsurance pricing will also stabilize. Their world-class modeling can project storm losses down to the decimal, but no model can predict how legal rackets create hurricane-esque losses in years with no hurricanes. With the right public policy, the insurance market will fire on all cylinders again. The oil change is long overdue. Kevin Comerer is a consultant and registered lobbyist with Rubin, Turnbull & Associates, in Tallahassee. He was previously legislative director for American Integrity Insurance Co. Monday, October 10 2022

Following Governor DeSantis' Emergency Orders 22-218 and 22-219, and pursuant to sections 252.63(1) and 627.4133(2)(d)1., Florida Statutes, the Florida Office of Insurance Regulation has issued an Emergency Order for Hurricane Ian regarding the extension of grace periods, limitations on cancellations and nonrenewals, deemers and limitations on "use and file" filings, along with other miscellaneous provisions. From September 28 – November 28, no insurer or other regulated entity may cancel, non-renew or issue a notice of cancellation or nonrenewal of a policy or contract except at the written request of the policyholder. For policies that would have been cancelled during this period, the insurer will extend coverage through November 28 or any later date identified by the insurer and the premium for the extended term will be pro rated for that specific term. This Emergency Order is issued to protect the public health, safety and welfare of all Florida policyholders. A copy of the order is available here. Answers to frequently asked questions regarding the Emergency Order is available here. Monday, October 10 2022

What’s making it so hard for Florida insurers to survive? Florida’s insurance rates have almost doubled in the past five years, yet insurance companies are still losing money for three main reasons. One is the rising hurricane risk. Hurricanes Matthew (2016), Irma (2017) and Michael (2018) were all destructive. But a lot of Florida’s hurricane damage is from water, which is covered by the National Flood Insurance Program, rather than by private property insurance. Another reason is that reinsurance pricing is going up – that’s insurance for insurance companies to help when claims spike. But the biggest single reason is the “assignment of benefits” problem, involving contractors after a storm. It’s partly fraud and partly taking advantage of loose regulation and court decisions that have affected insurance companies. It generally looks like this: Contractors will knock on doors and say they can get the homeowner a new roof. The cost of a new roof is maybe $20,000-$30,000. So, the contractor inspects the roof. Often, there isn’t really that much damage. The contractor promises to take care of everything if the homeowner assigns over their insurance benefit. The contractors can then claim whatever they want from the insurance company without needing the homeowner’s consent. If the insurance company determines the damage wasn’t actually covered, the contractor sues. So insurance companies are stuck either fighting the lawsuit or settling. Either way, it’s costly. Other lawsuits may involve homeowners who don’t have flood insurance. Only about 14% of Florida homeowners pay for flood insurance, which is mostly available through the federal National Flood Insurance Program. Some without flood insurance will file damage claims with their property insurance company, arguing that wind caused the problem. How widespread of a problem are these lawsuits? Overall, the numbers are pretty striking. About 9% of homeowner property claims nationwide are filed in Florida, yet 79% of lawsuits related to property claims are filed there. The legal cost in 2019 was over $3 billion for insurance companies just fighting these lawsuits, and that’s all going to be passed on to homeowners in higher costs. Insurance companies had a more than $1 billion underwriting loss in 2020 and again in 2021. Even with premiums going up so much, they’re still losing money in Florida because of this. And that’s part of the reason so many companies are deciding to leave. Assignment of benefits is likely more prevalent in Florida than most other states because there is more opportunity from all the roof damage from hurricanes. The state’s regulation is also relatively weak. This may eventually be fixed by the legislature, but that takes time and groups are lobbying against change. It took a long time to pass a law saying the attorney fee has to be capped. How bad is the situation for insurers? We’ve seen about a dozen companies be declared insolvent or leave since early 2020. At least six dropped out this year alone. Thirty more are on the Florida Office of Insurance Regulation’s watch list. About 17 of those are likely to be or have been downgraded from A rating, meaning they’re no longer considered to be in good financial health. The ratings downgrades have consequences for the real-estate market. To get a loan from the federal mortgage lenders Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae, you have to have insurance. But if an insurance company is downgraded to below A, Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae won’t accept it. Florida established a $2 billion reinsurance fund in May that can help smaller insurance companies in situations like this. If they get downgraded, the reinsurance can act like co-signing the loan so the mortgage lenders will accept it. But it’s a very fragile market. Ian could be one of the costliest hurricanes in Florida history. I’ve seen estimates of $40 billion to $60 billion in losses. I wouldn’t be surprised if some of those companies on the watch list leave after this storm. That will put more pressure on Citizens Property Insurance, the state’s insurer of last resort. Some headlines suggest that Florida’s insurer of last resort is also in trouble. Is it really at risk, and what would that mean for residents? Citizens is not facing collapse, per se. The problem with Citizens is that its policy numbers typically swell after a crisis because as other insurers go out of business, their policies shift to Citizens. It sells off those policies to smaller companies, then another crisis comes along and its policy numbers rise again. Three years ago, Citizens had half a million policies. Now, it has twice that. All these insurance companies that left in the last two years, their policies have been migrated to Citizens. Ian will be costly, but Citizens is flush with cash right now because it had a lot of premium increases and built up its reserves. Citizens also has a lot of backstops. It has the Florida Hurricane Catastrophe Fund, established in the 1990s after Hurricane Andrew. It’s like reinsurance, but it’s tax-exempt so it can build reserves faster. Once a trigger is reached, Citizens can go to the catastrophe fund and get reimbursed. More importantly, if Citizens runs out of money, it has the authority to impose a surcharge on everyone’s policies – not just its own policies, but insurance policies across Florida. It can also impose surcharges on some other types of insurance, such as life insurance and auto insurance. After Hurricane Wilma in 2005, Citizens imposed a 1% surcharge on all homeowner policies. Those surcharges can bail Citizens out to some degree. But if payouts are in the tens of billions of dollars in losses, it will probably also get a bailout from the state. So, I’m not as worried for Citizens. Homeowners will need help, though, especially if they’re uninsured. I expect Congress will approve some special funding, as it did in the past for hurricanes like Katrina and Sandy, to provide financial aid for residents and communities. Monday, October 10 2022

Hurricane Ian is going to affect commercial and personal property rates “significantly” – not just in Florida, predicted MarketScout. The Dallas-based insurance distribution and underwriting company released its quarterly Market Barometer of rate conditions in personal and commercial insurance lines. Overall, MarketScout reported an uptick of about 5.3% in the commercial market composite rate during the third quarter 2022, and an increase of about 4.6% for personal lines during the same period. n the second quarter, MarketScout said commercial rates increased just over 5.9%, virtually matching the rate increases of the first quarter. The focus of both reports was Hurricane Ian. MarketScout CEO Richard Kerr said the storm will “be a huge loss for insurers covering properties in Florida.” “Rates will be up dramatically in Florida for the foreseeable future,” he added in the personal lines Market Barometer. For commercial, Kerr said, “Losses from Hurricane Ian will significantly impact [property] rates in Florida and other wind exposed coastal states.” Commercial property rates were up nearly 7.7% in Q3. Rates for homeowners insurance in Q3 were up 4% for home under $1 million in value and 6% for home over $1 million. Kerr said high-value homes were already seeing more aggressive in Q3 because they are typically located in catastrophe-prone areas. Elsewhere in commercial lines, Kerr said MarketScout is seeing a softening in D&O and professional lines, but cyber insurance rates are “still increasing significantly” – up 23% in Q3.

The National Alliance for Insurance Education and Research conducted pricing surveys used in MarketScout’s analysis of market conditions. These surveys help to further corroborate MarketScout’s actual findings, mathematically driven by new and renewal placements across the United States. Friday, September 30 2022

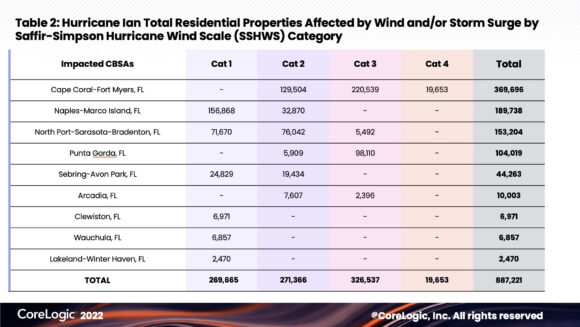

Wind and storm-surge losses from Hurricane Ian could reach as $47 billion in Florida alone, a figure made larger by inflation and rising interest rates, the property analytics firm CoreLogic said in a new analysis. “This is the costliest Florida storm since Hurricane Andrew made landfall in 1992 and a record number of homes and properties were lost due to Hurricane Ian’s intense and destructive characteristics,” said Tom Larsen, associate vice president for hazard and risk management at CoreLogic. Wind-damage losses in Florida, where Ian made landfall Wednesday afternoon near Fort Myers, are expected to be between $22 billion to $32 billion for residential and commercial properties. Storm-surge damage could add another $6-$15 billion, CoreLogic calculated. The analysis was based on high-resolution imaging and storm-surge computer modeling, the firm said. CoreLogic said its calculations include insured and uninsured losses, and Hurricane Ian has yet to make another predicted landfall in South Carolina as a Category 1 storm on Sept. 30, but to begin to put Hurricane Ian into a historical perspective, below is a list of the costliest U.S. hurricanes to the insurance industry. With inflation at a 40-year high, interest rates near 7%, and labor and building materials in short supply, recovery will be slow and difficult. “Hurricane Ian will forever change the real estate industry and city infrastructure,” Larsen said in a news release. “Insurers will go into bankruptcy, homeowners will be forced into delinquency and insurance will become less accessible in regions like Florida.” Besides winds and surge on Florida’s southwest coast, Ian also caused widespread flooding inland in Florida. The storm by Friday morning had weakened, then strengthened as it aimed for coastal South Carolina with 85-mph winds, the National Weather Service reported. Larsen said the storm will likely be a wake-up call, spurring stronger building codes and more resilient infrastructure. ICEYE, the satellite imagery firm, reported that almost 84,000 properties in coastal southwest Florida were affected by storm surge and flooding during Ian, as of Thursday afternoon. Most of those felt less than two feet of water, but 284 were hit by floodwaters above eight feet, the company reported. Thursday, September 29 2022

Hurricane Ian continued to churn through central Florida Thursday morning, leaving widespread flooding and wind damage in its wake. It was too early to know the extent of property insurance claims from the storm, although a few analysts and officials offered some preliminary estimates. Some in the industry are now worried that extensive losses from the storm, which made landfall north of Fort Myers with an estimated 12-foot storm surge, could be devastating for Florida’s largest and fastest-growing property insurer – the state-created Citizens Property Insurance Corp. Citizens’ CEO Barry Gilway said Wednesday that preliminary estimates have put claims at about 225,000 and potential exposure at about $3.8 billion, a spokesman for the insurer said. That’s likely not enough to force an assessment on policyholders, he said, in response to a reporter’s question. A former deputy Florida insurance commissioner, Lisa Miller, warned that if losses exceed the corporation’s reinsurance coverage, Citizen policyholders could see a 15% surcharge for all three of Citizens’ accounts – as much as 45% per property. If Gilway’s estimate holds true, it would mean Citizens avoided a worst-case scenario with the powerful storm. The Office of Insurance Regulation’s quarterly reports, based on insurer data, shows that for the five coastal counties most affected by Ian, Citizens holds more than 60,000 policies with a total exposure of at least $17.5 billion. The OIR’s Quarterly and Supplemental Report, known as QUASR, shows that another insurer, the Palm Beach Gardens-based Olympus Insurance Co., has significant exposure. For the hard-hit coastal counties of Manatee, Sarasota, Desoto, Charlotte and Lee, Olympus had some 13,800 policies in the second quarter of this year, with $11.3 billion in exposure. The report does not give a complete picture of the market. A number of Florida-based insurers do not report their data or allow them to be made public, calling the information “trade secrets.” But the Olympus numbers are notable. Statewide, the firm had some 79,000 policies and $233 million in total written premium. Olympus CEO Steve Bitar could not be reached for comment about the Ian exposure. Other insurers with billions in exposure in the five coastal counties include:

Insurance industry insiders said it’s difficult to judge which carriers are most vulnerable without knowing the extent of their reinsurance programs, information that is not usually made public. Statewide, claims from Hurricane Ian could total as much as $30 billion, a Wells Fargo analyst told Barron’s financial news site. Another analyst told Barron’s that the storm could also lead to higher reinsurance premiums, a tough call for some insurers already struggling with reinsurance costs that spiked as much as 50% this year. Meanwhile, the Florida OIR said that insurers should begin daily reporting of catastrophe claims as early as Friday, Sept. 30, through Friday, Oct. 7. The data should be reported each day before noon Eastern time, through the simplified 2022 catatastrophe reporting form, or CRF, OIR said in a bulletin Wednesday. Insurance Commissioner David Altmaier also issued an emergency order that requires insurance companies to extend deadlines for insureds. For any policy or other notice that requires policyholders to provide information by Sept. 28, the time has been extended to Nov. 28. Insurers also are barred from cancelling or non-renewing policies until after Nov. 28, the order reads. All notices that were mailed after Sep. 18 must be withdrawn and reissued to insureds after the November date. In addition, insurers should not cancel residential policies on damaged homes in Florida until 90 days after the dwelling has been repaired. Rate and form filings known as “use and file,” which are not reviewed by OIR until later, are suspended for now. Hurricane victims that utilize premium financing and have lost their homes or jobs should contact the OIR. “Victims of Hurricane Ian will receive an automatic extension of time to and including November 28, 2022, to bring their accounts up to date,” the order noted. “No late charges will be applied to any late payments received which were due on their accounts between September 28, 2022 and November 28, 2022.” The OIR also said it expects claims to be paid in a timely manner. “Given the strength and size of Hurricane Ian, its expected catastrophic effect on Florida, and its potential impact on hundreds of thousands of policyholders, the Office expects all insurers and regulated entities to implement processes and procedures to facilitate the efficient payment of claims,” the order reads. “This includes critically analyzing current procedures and streamlining claim payment processes as well as using the latest technological advances to provide prompt and efficient claims service to policyholders.” |

Personal Service at Internet Prices!

|

© Olson & DiNunzio Insurance Agency, Inc., 2008

2536 Northbrooke Plaza Drive; Naples, FL 34119

Doing Business in the State of Florida

P: 239-596-6226; F: 239-596-1620; E: info@olsondinunzio.com

Featuring the cities of Naples, Bonita Springs, Marco Island and Estero Florida. Providing them the highest quality insurance and unbeatable rates.